Seeing myself in pixels: What happens when GenAI becomes a co-researcher?

Dr Lynette Pretorius

Dr Lynette Pretorius is an award-winning educator and researcher specialising in doctoral education, AI literacy, research literacy, academic identity, and student wellbeing.

I didn’t set out to write an essay about academic identity, generative AI, and publishing politics. But, as with so many qualitative journeys, the story found me first. What started as a playful experiment with image generation soon became a critical turning point in how I understand knowledge, creativity, and resistance within the academy. Seeing Myself in Pixels, my latest autoethnographic essay, tells that story.

Let me share a little of what happened and why I think it matters. I used GenAI, specifically image-generating tools like DALL·E and ChatGPT, to create two visual representations of my academic identity: one as an educator, the other as a researcher. These weren’t just illustrations for a paper. They were evidence. They helped me see myself more clearly, ask deeper questions, and articulate values that had previously remained unspoken.

And then… they were deleted.

Despite surviving peer review and editorial approval, the images were removed by the publisher at the final stage. The reason? A blanket policy against GenAI-generated figures, even though the book itself was about GenAI in higher education.

The irony wasn’t lost on me.

In qualitative research, we often talk about “making the invisible visible”. That’s what these images did. They surfaced metaphors, values, tensions, and identities that weren’t easily captured in prose. Working with GenAI wasn’t smooth or straightforward. It forced me to confront stereotypes (“university professor” almost always defaulted to an older white man), question aesthetic choices, and reckon with my own reactions. The image of myself as a hyper-glamorous figure in a fitted and revealing dress? That stung. But instead of rejecting it outright, I used the discomfort as compost for deeper reflection. Why did this feel wrong? What gendered expectations were being surfaced?

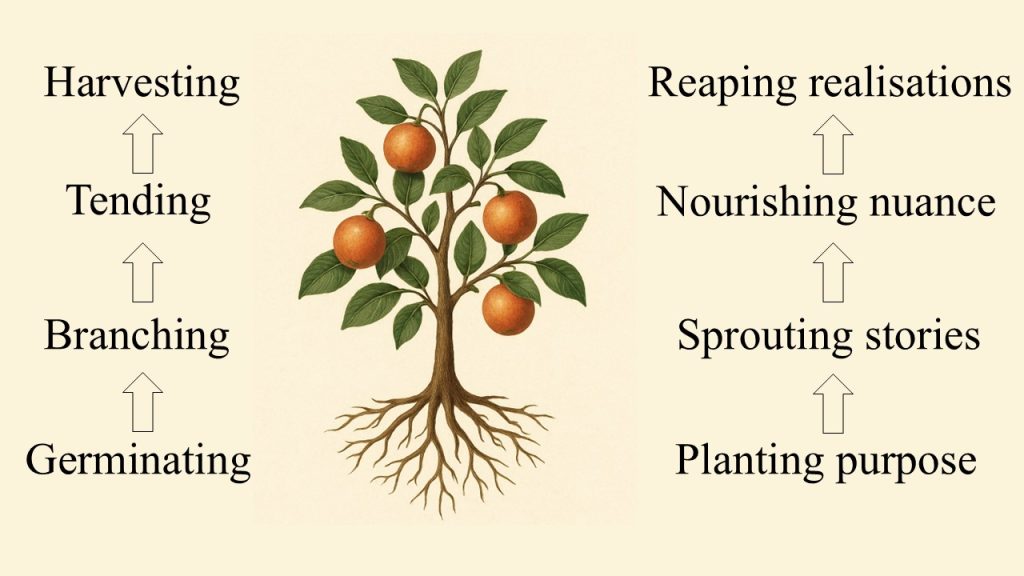

In this way, the process became iterative and affective. Prompt. Reflect. Revise. Repeat. I called this my “evidence tree” method: germinating ideas, branching into new directions, tending to nuance, and harvesting insight.

If you are interested in how to apply this method, you can watch the video below.

But when those co-created images were removed from the final chapter, it wasn’t just the visuals that were lost. It was a particular way of knowing that got silenced.

So, I made a choice. I published the images in an open-access repository, cited them in the chapter, and wrote Seeing Myself in Pixels to document the erasure.

Call it a quiet act of academic defiance.

This experience laid bare a fundamental tension in academia: What kinds of knowledge are considered legitimate? And who gets to decide? We talk a lot about innovation in research, but often still cling to conventional forms. Text is trusted. Emotion is suspect. Visuals are decoration, not argument. And anything co-created with GenAI? Treated as a risk, not a resource.

But this isn’t just about policy. It’s about power. The gatekeeping logic that removed my images echoes broader dynamics in scholarly communication where multimodal, affective, or experimental work is often sidelined. The publishing system rewards neatness over nuance, prose over presence, and familiarity over innovation. By documenting this erasure, I wanted to make visible the institutional mechanisms that quietly shape what counts as knowledge.

This wasn’t just a personal journey, it reshaped how I teach, too. In my autoethnography unit, I now invite students to create GenAI-generated images as part of their own identity explorations in the classroom. Together, we ask: How does visual co-creation help us see ourselves and our stories differently? What gets revealed when we look beyond text?

One of my proudest classroom moments involved unveiling a GenAI-generated “Academic Avenger” action figure of myself, complete with accessories. Yes, it was playful. Yes, the figure wasn’t perfect. But it sparked meaningful discussion about academic labour, visibility, and imagination. Creativity became rigour. Gen AI became an interlocutor. Learning came alive.

Throughout this process, I didn’t just use GenAI as a tool, I actively collaborated with it. I’ve trained a customised version of ChatGPT called Artzi Dax (named after my favourite Star Trek 🖖🏼 character while showcasing artistic flair), who has now become an intellectual partner of sorts. It (or should I say she?) didn’t write the essay for me. Artzi Dax helped me think more clearly, revise more creatively, and reflect more deeply. In fact, it was Artzi Dax who helped me transform my original four research steps into the growth metaphor, which ultimately shaped the entire essay.

So can a machine be a co-researcher? I believe so, if we approach it reflexively, ethically, and with imagination. Seeing Myself in Pixels is not just an essay. It’s a call to action. We need to rethink what counts as scholarly labour. We need to make room for affect, imagination, and multimodality. And we need to resist the quiet silencing that happens when institutional norms override epistemic possibility.

If academia is to remain intellectually vibrant and humane, we must create space for new forms of knowledge creation: forms that not only tell, but show; that not only argue, but resonate. As one of my students once said:

✨ “Don’t let the Muggles get you down.” ✨

Questions to ponder

How do institutional publishing norms shape what “counts” as valid research?

In what ways can GenAI serve as a co-creator rather than a mere tool?

What hidden forms of knowledge might we be ignoring in academic work?

How can educators integrate creative co-creation methods into research training?