Reclaiming our words: how generative AI helps multilingual scholars find their voice

Dr Lynette Pretorius

Dr Lynette Pretorius is an award-winning educator and researcher specialising in doctoral education, AI literacy, research literacy, academic identity, and student wellbeing.

Redi Pudyanti

Contact details

Redi Pudyanti is an educator and researcher pursuing her PhD on the influence of local wisdom on graduate employability. Her other research interests are Indigenisation, decolonisation, and generative AI.

Acknowledgement: This blog post extends our presentation at the Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference 2025. We acknowledge the other co-authors of our paper, as it was a truly collaborative project: Huy-Hoang Huynh, Ziqi Li, Abdul Qawi Noori, and Zhiheng Zhou. As the South African proverb says: “If you want to run fast, run alone; if you want to run far, run together”.

You can listen to the HERDSA2025 presentation below.

In the halls of academia, where prestige often correlates with fluency in a particular kind of English communication, having a voice can feel like a privilege, not a right. For multilingual scholars, this can create a disconnect between who they are and what academia expects of them. These scholars have rich and diverse intellectual contributions, but these are often filtered, flattened, or forgotten by the English-language customs of academia. This isn’t just about grammar or vocabulary. It’s about whose knowledge counts, whose voice is deemed legitimate, and how power circulates in scholarly spaces.

Academic writing is often seen as a neutral skill: something that anyone can learn with enough practice, feedback, and hard work. In reality, though, this idea of neutrality is misleading. Beneath the surface, academic writing carries a host of hidden expectations: about how to structure an argument, what kind of tone sounds “professional”, which sources are seen as credible, and even what types of ideas are considered valuable or “good”. These expectations aren’t universal: they’re shaped by English-speaking academic traditions and Western ways of thinking.

For multilingual scholars, especially those coming from different cultural and educational backgrounds, this can feel like stepping into a performance where the rules haven’t been explained. They’re expected not just to write clearly, but to sound a certain way: to mirror the phrasing, logic, and stylistic choices of native English speakers who have been immersed in this Western ways of thinking from an early age. It’s a bit like being asked to join a play mid-scene, in a language that’s not your own, with the added pressure of sounding polished and convincing. The result is often a quiet and persistent pressure to conform: to smooth out cultural expression, to set aside familiar ways of knowing, and to rewrite one’s voice to match what academia deems “legitimate”. In this context, writing isn’t just about communicating ideas, it becomes a test of belonging.

This experience can be deeply isolating. When your ideas are dismissed because they don’t fit a particular format, or when you constantly feel like your writing is being judged through the lens of language proficiency rather than substance, it can leave you feeling invisible. For many multilingual scholars, it’s not just a matter of learning the rules; it’s the emotional weight of having to silence parts of who you are just to be taken seriously. Over time, this can lead to a sense of marginalisation, where your contributions feel undervalued, and your cultural perspective feels out of place. It’s certainly not that these scholars lack ideas or insight; it’s that the academic system often fails to make room for how those ideas are expressed.

We have found that these challenges can make academic life feel like a constant uphill battle, especially when the very structures meant to support learning and innovation exclude our ways of thinking and being. Yet, rather than remain silent or adapt unquestioningly, we have been actively seeking new ways to engage with academia in ways that honour both our cultural identities and scholarly ambitions. This is where our latest research began: with a shared desire to not only survive academia, but to reshape it. Through community, reflection, and the careful integration of generative AI, we began to imagine what a more just and inclusive academic future could look like.

Writing together, thinking together: a decolonising vision for academic writing

Our new paper offers a timely vision of the future: one where academic spaces are reimagined as inclusive, relational, and linguistically diverse, and where generative AI is embraced not as a threat to academic integrity and rigour, but as a partner in knowledge creation. To develop this vision of academia, we combined the Southern African philosophy of Ubuntu (a philosophy that says, “I am because we are”) with collaborative autoethnography and the strategic use of generative AI to reframe generative AI as a relational tool for epistemic justice. As noted in another blog post, epistemic justice is about fairness: it ensures that everyone’s voice and knowledge are equally respected, no matter where they come from or how they express themselves. In our vision of a more just and inclusive academic future, multilingual scholars will feel empowered to contribute fully, confidently, and in ways that honour their linguistic and cultural identities within global scholarly conversations.

One of the most important parts of our study was how we chose to think about and use generative AI. Ubuntu reminded us that we’re shaped by our relationships with others, and that knowledge and growth are shared, not owned by any one person. In many academic settings, writing is treated as something you do alone. Seeing academic writing through the Ubuntu philosophy, however, we saw knowledge creation and dissemination as something academia should do together. In our group, we gave each other feedback not to criticise, but to support and learn from one another. In this spirit, generative AI became more than just a helper. It became a kind of thinking partner that joined us in our conversations, helping us express our ideas more clearly while still keeping our voices true to who we are. Our generative AI use empowered us while also honouring our identities as multilingual speakers engaging with global academia.

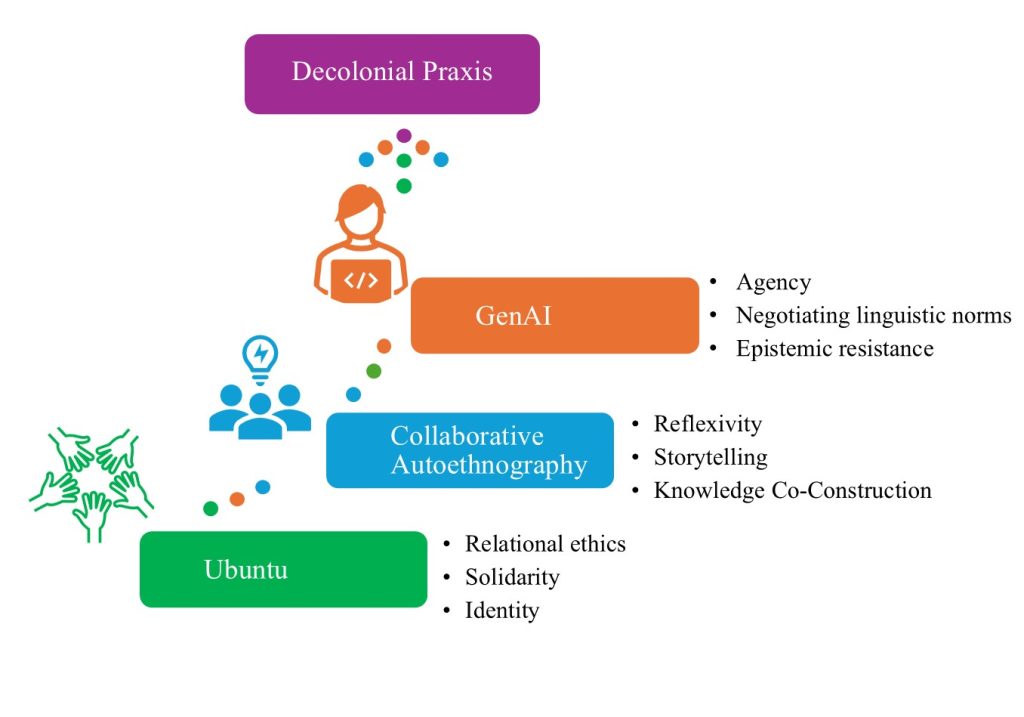

At its heart, our work is about challenging the status quo in academia: we aim to decolonise how knowledge can be created and shared in academia. As shown in our figure below, we started with Ubuntu, a philosophy that puts relationships, community, and shared responsibility at the centre. From there, we used a method called collaborative autoethnography, which allowed us to tell our personal stories, learn from each other in a supportive, reflective way, and explore the cultural complexities present within academia. Then we brought in generative AI, not to make our writing faster, but to help us express our ideas more clearly, question academic norms, and speak up in ways that felt true to ourselves. These three elements aren’t separate steps. Like threads in a tapestry, they are woven together to create a new way of doing research. Together, they helped us imagine a more inclusive kind of academic voice: one that’s ethical, shared, and shaped by many perspectives, not just one. The dots in the diagram show how these ideas flow between people, values, and technology, all working together to build a better future for academic work.

Stories of reclamation and agency

One of the most vivid examples from the study involves the translation of a Chinese idiom which, when processed through a conventional tool, was reduced to a flat literalism: “seeing flowers in the mist, looking at the moon in the water”. While technically accurate, the translation missed the metaphorical essence of the idiom. When Ziqi, one of the authors, posed the same phrase to ChatGPT, the response captured both the poetic beauty and interpretive depth she needed by offering: “The situation is shrouded in mystery, constantly shifting, and challenging to grasp”. In that moment, the idiom didn’t just survive translation, it transcended it. For Ziqi, this wasn’t merely a linguistic success; it was a profound moment of affirmation. Her cultural ways of knowing embedded in the metaphor’s symbolism and rhythm didn’t have to be abandoned or diluted to be legible in academic English. They could be translated with meaning, not despite it.

For others in the group, generative AI proved equally transformative in different contexts. It supported the generation of constructive feedback, assisted in structuring complex presentations, and offered clarity around dense theoretical frameworks. In Redi’s case of balancing the demands of doctoral research with motherhood, generative AI became an unexpected ally in maintaining wellbeing. Whether generating weekly schedules, planning meals, or brainstorming research questions, it helped her lighten the cognitive load, carving out space for reflection, family, and rest.

Importantly, though, our paper isn’t a love letter to generative AI. We are acutely aware of the ethical tensions. Generative AI tools are shaped by the biases of their training data, data which are often steeped in colonial logics, linguistic hierarchies, and Western-centric perspectives. The risk of overreliance or uncritical adoption is real. Yet, what shines through in our reflections is not techno-optimism, but intentionality. We didn’t blindly accept what generative AI offered. Instead, we engaged with it critically, revising, interrogating, and adapting output to ensure the content preserved cultural nuance and scholarly integrity.

Implications for academia

What we did wasn’t about quietly fitting in or changing ourselves to match the usual expectations of academic writing. It’s something more powerful: it was an act of academic reclamation. We used generative AI thoughtfully and with care, not to erase our voices, but to amplify them. Our voices are shaped by different cultures, languages, and ways of thinking, and these types of voices don’t always fit neatly into the typical mould of English-speaking academia. By working with generative AI, not just relying on it, we found ways to express our ideas more clearly without losing who we are. We’re not just trying to keep up, we’re helping to change what academic writing can be. We’re showing that it’s possible to honour cultural and linguistic diversity in research, and that there’s real value in broadening what counts as a “legitimate” academic voice. In doing so, we’re not just joining the conversation, we’re reshaping it. Prompt by prompt, paragraph by paragraph, we’re building an academic world that listens to more voices, tells more stories, and reflects more diverse ways of knowing.

Our study calls on educators, institutions, publishers, and policy-makers to rethink what counts as “good writing” and whose voices are heard in academic discourses. It invites everyone to question the academic orthodoxy that frames multilingual ways of thinking as flawed or generative AI use as inherently dishonest. It shows that when used ethically and reflexively, generative AI can level the playing field, not by simplifying scholars’ ideas, but by enabling them to be expressed more fully. By integrating Ubuntu, collaborative autoethnography, and generative AI, we empowered each other and contributed to decolonising the academy by advancing non-traditional voices. Our research presents a compelling vision for a more inclusive academy: one where multilingualism is celebrated, not hidden, and where academic voice is something to be reclaimed, not earned through conformity. As Lynette notes in the paper:

I have also had many discussions with colleagues in other countries who seem to believe that the use of generative AI has led to the loss of academic rigour or critical thinking in students’ work. They either lament that they cannot clearly detect AI written work with tools such as Turnitin, or claim that whenever they see the words “delve” or “tapestry” they know that it is written by AI and should therefore be considered as cheating. […] I see this viewpoint as a form of academic orthodoxy, where written academic work is considered “rigorous” only when it has been written as it has always been. […] I wonder whether the same debates were circulating in academia when the typewriter was invented and those who used to write academic missives by hand thought that the typewriter would be a danger to academic rigour?

By the way, Lynette also shared two other studies at this year’s HERDSA conference. Follow the links below to explore those studies in more detail.

If you are interested in learning more about this study, you can also listen to this podcast about the paper.

Questions to ponder

Whose standards define “good” academic writing? How do linguistic norms in academia privilege certain voices while marginalising others? In what ways might generative AI disrupt or reinforce these norms, and what responsibilities do scholars have in shaping its use?

Can technology be decolonial? Given that most generative AI tools are trained on predominantly Western data sources, is it possible for them to support decolonial knowledge practices? What conditions would need to be met for generative AI to serve as a truly inclusive and relational academic partner?

What does ethical generative AI use look like? Reflecting on the Ubuntu-inspired approach described in the post, how can scholars use generative AI tools ethically, without losing their cultural specificity or scholarly voice? How might institutions better support this kind of critical and agentive generative AI engagement?

This is one of the most powerful and human-centered explorations of AI in academia I’ve read. The Ubuntu approach and collaborative autoethnography offer a visionary path toward inclusive scholarship. Thank you for reminding us that AI doesn’t have to erase identity—it can help amplify it, if used with care and intention.

Thanks for your kind comment – we are glad you found our post so powerful 🙂